Much of History Remains Unwritten

From the British and Gaelic bards, to the Griots of West Africa, to the stories about lineage that we grow up hearing from our family members, oral traditions are some of the oldest and most consistent ways of passing down information from one generation to the next. Sometimes set to music or written in poetry, these histories are often preserved in culturally significant and unique ways.

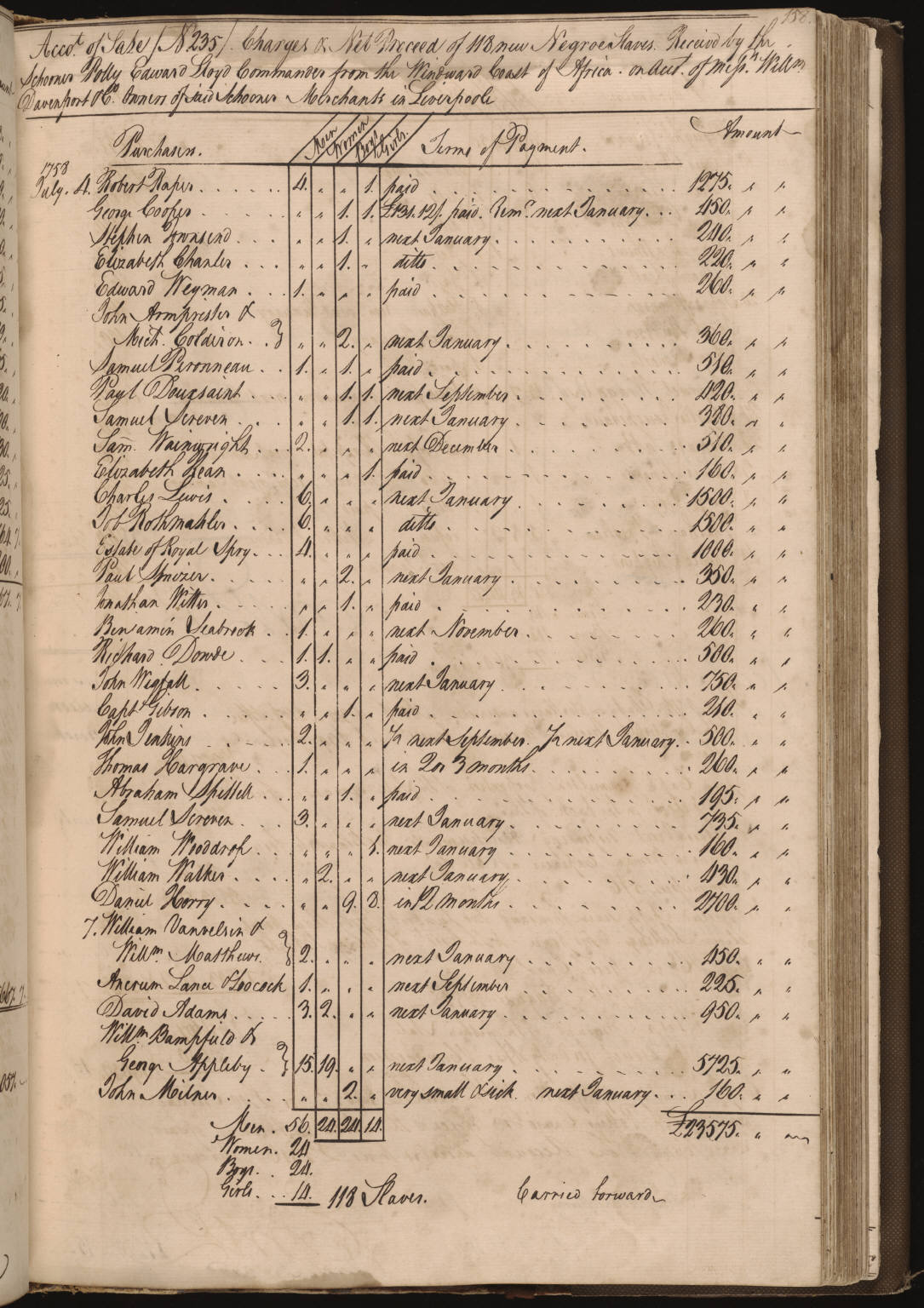

Modern practice privileges histories that are written down. We tend to think of oral histories like we would a game of telephone, fearing that the story is altered each time it's told until finally, the information is so skewed and glamorized it barely resembles the original events. We doubt people’s memories and call into question the bias of ancestors. Therefore, oral histories are frequently dismissed as unreliable historical sources, though in the United States, it's rare that details about most nonwhite or poor white Americans regularly appear in documentary evidence. We fail to recognize that what is and what is not remembered can provide important information and context about the past and people's individual and collective lives.

Modern practice privileges histories that are written down. We tend to think of oral histories like we would a game of telephone, fearing that the story is altered each time it's told until finally, the information is so skewed and glamorized it barely resembles the original events. We doubt people’s memories and call into question the bias of ancestors. Therefore, oral histories are frequently dismissed as unreliable historical sources, though in the United States, it's rare that details about most nonwhite or poor white Americans regularly appear in documentary evidence. We fail to recognize that what is and what is not remembered can provide important information and context about the past and people's individual and collective lives.