And 10 Million Patents

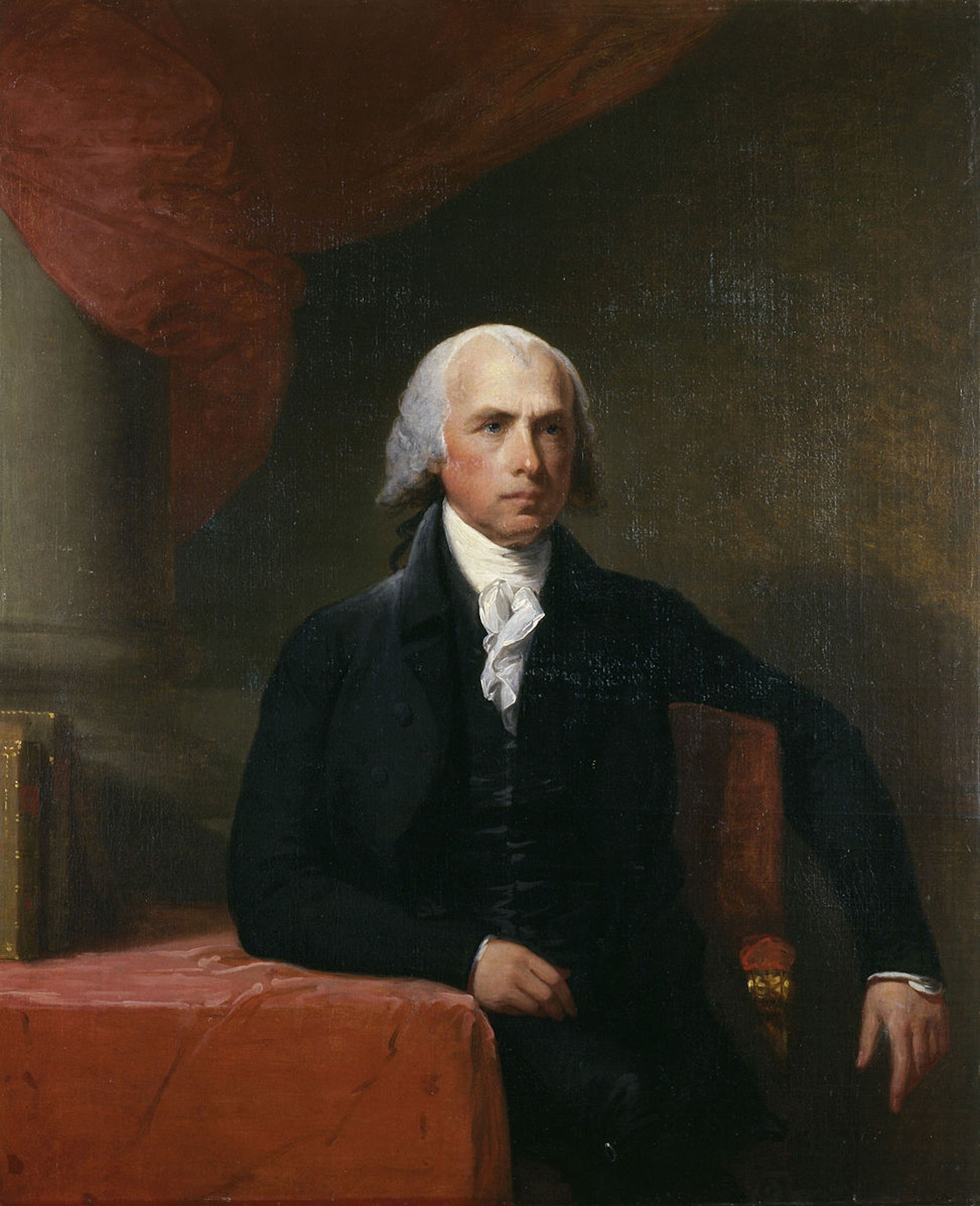

Portrait of James Madison, comissioned by Honorable James Bowdoin III. Madison served in the House of Representatives and as Jefferson's Secretary of State, before serving as President from March 4, 1809 until March 4, 1817.

Though known mostly as the 4th President and for his contributions to the Constitution, it was in fact, James Madison, who set the stage for generations of innovation.

The Constitutional Convention

In a lesser-known moment of the Constitutional Convention, it was Madison who inserted patent protection into the debates.

The Constitutional Convention. Oil on canvas. Artist: Junius Brutus Stearns. Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

On the sweltering day of August 18, 1787, as the delegates hammered out the powers to be given to Congress, Madison proposed that Congress be empowered “to encourage, by proper premiums & Provisions, the advancement of useful knowledge and discoveries." (Perhaps Madison would have found it “useful” for someone to have invented air conditioning right about then.) The Committee of Detail took Madison’s proposal, combined it with recommendations by Madison and Charles Pinckney for literary copyright protections, and came up with the Copyright and Patent Clause:

“[The Congress shall have power] To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” - United States Constitution, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8.

“[The Congress shall have power] To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

United States Constitution, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8

Who could disagree with that? The Convention approved the clause unanimously without further discussion. Madison defended this Congressional power as essentially a no-brainer, writing In Federalist 43: “The utility of this power will scarcely be questioned. The copyright of authors has been solemnly adjudged, in Great Britain, to be a right of common law. The right to useful inventions seems with equal reason to belong to the inventors. The public good fully coincides in both cases with the claims of individuals. The States cannot separately make effectual provisions for either of the cases...” For Madison, the right to intellectual property was based in natural rights philosophy; under the labor theory of property, you have a right to what you produce with your own labor, whether physical or mental.

An Advertisement of The Federalist. Wikimedia Commons.

The First Congress

With the ratification of the Constitution, the First Congress used its powers to create the Patent Act of 1790. This set up a three-member patent review board, consisting of the Secretary of State, Secretary of War, and the Attorney General. (Apparently it occurred to no one that these Cabinet members had other things on their plates. Even Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State and unofficial gadget guru, was overwhelmed by the stream of patent applications.) In 1793 Congress streamlined the process, eliminated the review board, and gave the job of granting patents to a single clerk in the State Department. Now an inventor only had to submit a model, swear that the invention was original, and pay a $30 fee.

Patent applications continued to pour into the State Department as inventors came up with new and improved versions of machines and technical processes. Perhaps Congress had underestimated the American urge to tinker. A lowly file clerk couldn’t be expected to distinguish genuinely new ideas from ones that had already been patented. Congress, however, was unwilling to set up a separate Patent Office.

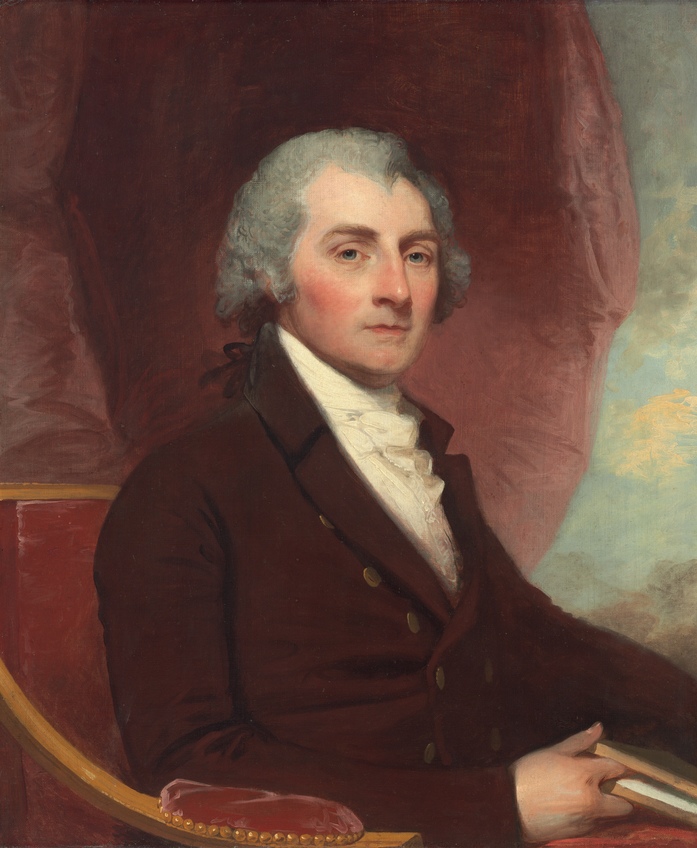

Understanding the importance of innovation for the American economy, Madison devised a work-around in 1802 during his term as Secretary of State. Not only did Madison set up a Patent Office within his State Department, he found just the right person to superintend it. William Thornton was something of a renaissance man: a medical doctor, an architect (whose designs included the original United States Capitol building), and an inventor himself.

Dr. William Thornton. Wikimedia Commons.

The First Patent Office

Thornton was devoted to the Patent Office, where he served for the next 26 years. When Congress underfunded and understaffed the office, Thornton, along with his wife Anna Maria Brodeau Thornton, resorted to copying out patents at home after hours. During the War of 1812, as British troops entered Washington on August 24, 1814 and began to burn the public buildings, Thornton made a desperate plea to save the hundreds of inventors’ models stored at the Patent Office. Destroying this evidence of human ingenuity, Thornton claimed, would be on par with the notorious burning of the library of ancient Alexandria. After meeting with British officers in three different locations, Thornton secured a promise that the Patent Office would be spared.

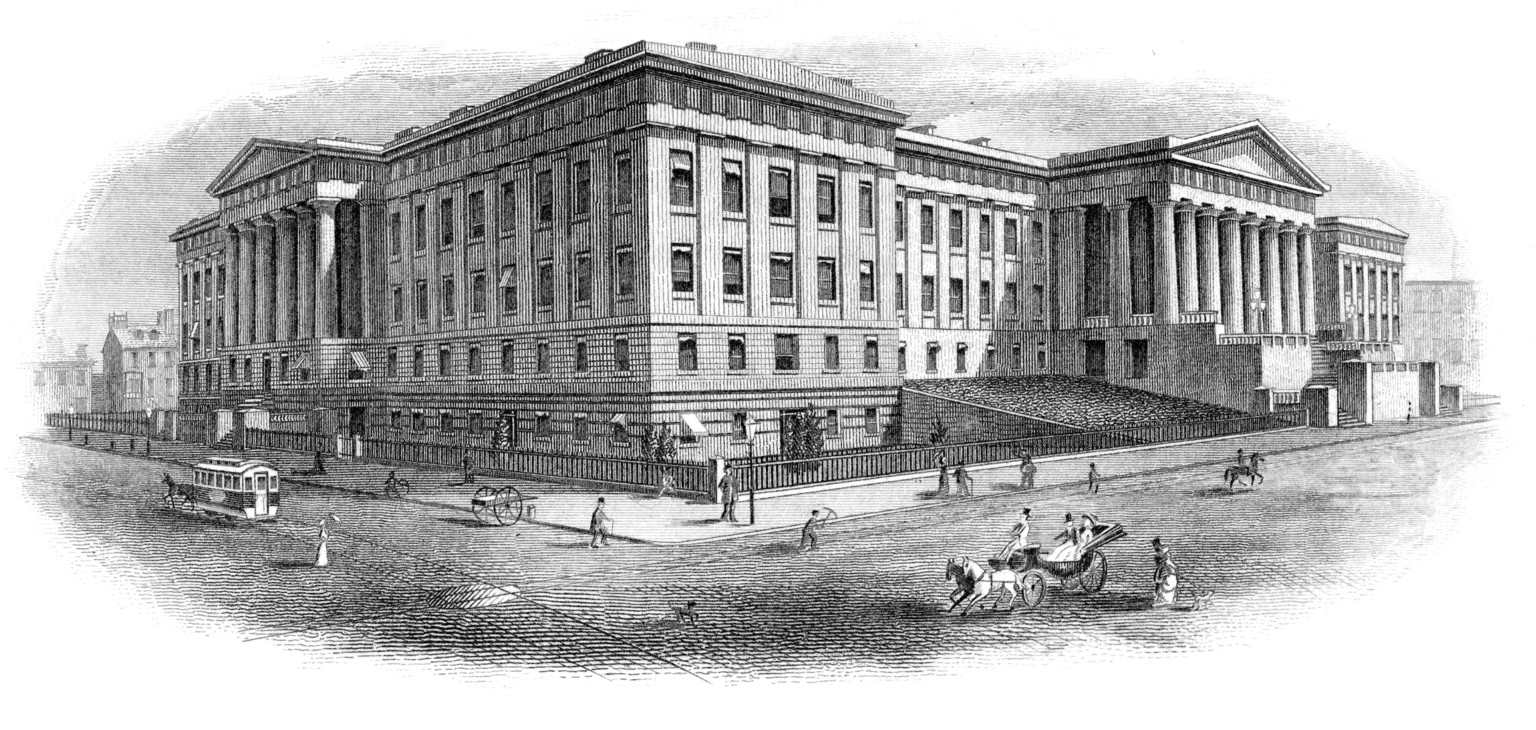

United States Patent Office, circa 1880. Congress authorized the construction of this building as the Patent Office in July 1836, shortly after Madison's death. Today it houses the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. Wikimedia Commons.

Madison made another appointment that would have an important influence on the future of patents. As president, Madison named Joseph Story to become a Supreme Court Justice in 1811. Justice Story served for the next 34 years, writing 40 opinions on patent law cases. Madison had no way of knowing that his nominee would one day be called “an architect of American patent law.” Yet Story’s appointment is just one more way that Madison’s legacy continued to affect intellectual property rights, technological innovation, and economic growth.

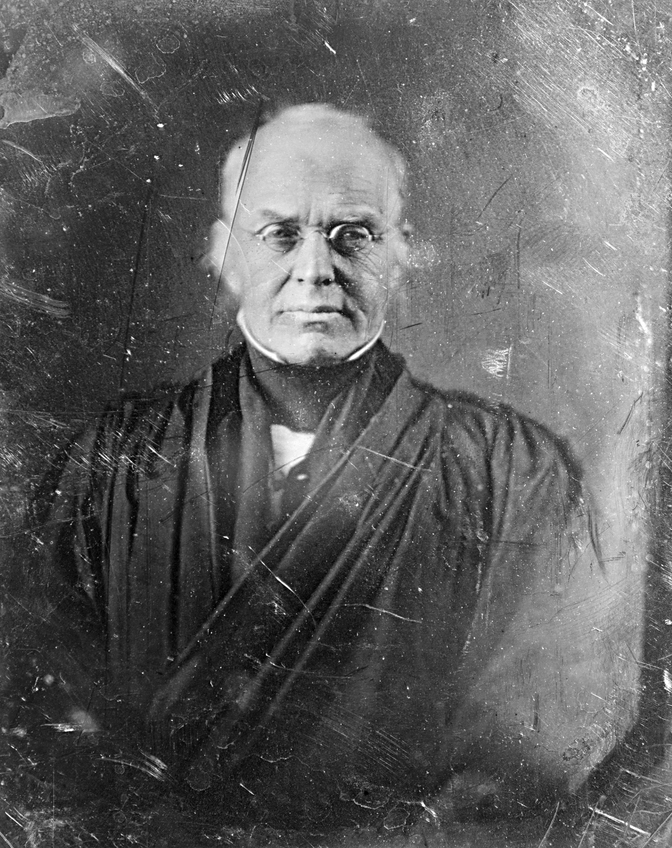

Daguerreotype of Joseph Story, 1844. Wikimedia Commons

American Innovation

Many aspects of the patent process have changed since James Madison spoke up for “the advancement of useful knowledge and discoveries" on that sultry summer day at the Constitutional Convention. Yet, his contribution to intellectual property protection is undeniable. And thanks to Madison’s 1787 proposal, Willis Haviland Carrier was able to receive U. S. Patent number 808,897 in 1906 – for something we're all relying on right about now...

The air conditioner.

The air conditioner.