Published: November 21, 2018

Question

1. How many high school seniors do you think can identify slavery as the root cause of the civil war?

2. How many high school seniors know that slavery is protected by our nation's founding document?

2. How many high school seniors know that slavery is protected by our nation's founding document?

Answer

1. A mere 8%.

2. Only 22%.

2. Only 22%.

The National Summit on Teaching Slavery

In a recent study conducted by The Southern Poverty Law Center's Teaching Tolerance project, researchers found that the topic of slavery is often mistaught, from factual errors to misrepresentation of how the institution of slavery shaped fundamental beliefs and modern views of race. The way our students and teachers are conceptualizing slavery had been found to be misguided, skewing the conversations we're having, the "facts" we're presenting, and the opinions we're forming and passing on.

Maureen Costello, Director of Teaching Tolerance, Southern Poverty Law Center, participates in an afternoon discussion at the National Summit on Teaching Slavery at James Madison's Montpelier on Saturday, Feb. 10, 2018, in Montpelier Station, Va. (Andrew Shurtleff/AP Images for James Madison's Montpelier)

On a wet weekend in February 2018, a group of 49 educators, curators, scholars, activists, museum and historic site professionals, and descendants of people who were once enslaved gathered at James Madison’s Montpelier at the inaugural National Summit on Teaching Slavery.

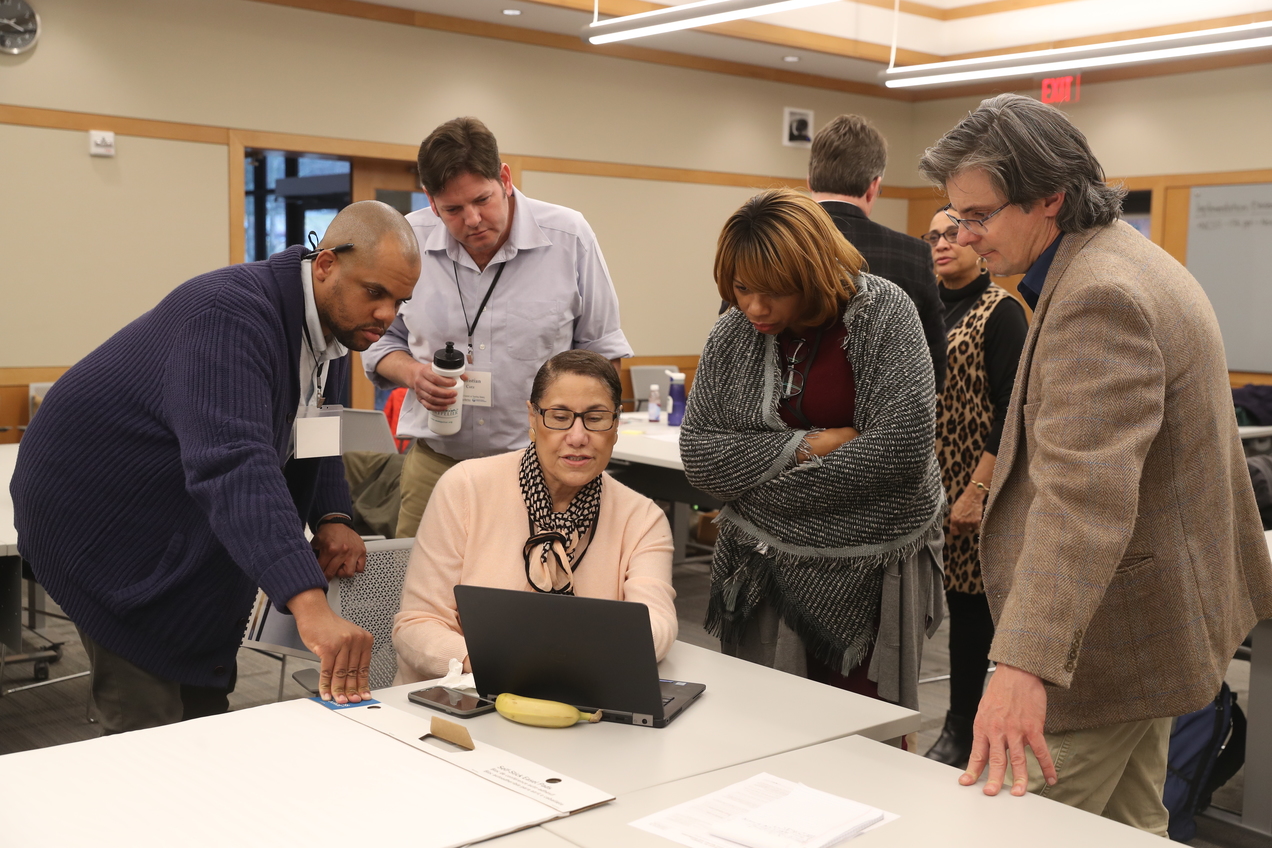

A group of participants engage in a breakout session during the National Summit on Teaching Slavery (Andrew Shurtleff/AP Images for James Madison's Montpelier)

This partnership between James Madison’s Montpelier and the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, is the first national, interdisciplinary effort to formulate a recognized model for best practices in descendant engagement and slavery interpretation. The summit builds on the successful model of descendant engagement – rooted in best practices for historical research, community dialogue, exhibition design, and historic preservation – implemented during the creation of Montpelier’s new, award-winning slavery exhibition, The Mere Distinction of Colour.

Kat Imhoff, President & CEO of The Montpelier Foundation, and Brent Leggs, Director, African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, in an exhibition space of The Mere Distinction of Colour at James Madison's Montpelier (Andrew Shurtleff/AP Images for James Madison's Montpelier)

"Our country must come to grips with our past," says Montpelier President & CEO, Kat Imhoff. "This is an important step towards institutions consistently telling a more honest and equitable version of history."

Participants came from around the country, and included Evelyn Higginbothom, Victor S. Thomas Professor of History and African American Studies at Harvard University, Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President, Director of Interpretation of Eastern State Penitentiary, Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Associate Professor of History at The Ohio State University, and Greg Carr, Associate Professor of Africana Studies and Chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University.

"This is an important step towards consistently telling a more honest and equitable version of history."

Kat Imhoff, President & CEO of The Montpelier Foundation

Dr. Evelyn Higginbotham participates in a small group discussion (Andrew Shurtleff/AP Images for James Madison's Montpelier)

Over the course of the weekend the group engaged in discussions and debates about the best ways to teach the history and legacies of slavery. Participants carefully considered how historic sites can successfully talk to visitors about slavery and its lingering effects on society while also building community. They considered the seminal question of "how can the stories and experiences of enslaved people best be relayed to visitors? How can descendants of the enslaved play a role in sharing the experiences of their ancestors?" From there, they analyzed how different museums, historic sites, and cultural institutions explain or portray such difficult, painful history, and brainstormed around how sites should teach visitors about slavery more engagingly and inclusively.

Why Montpelier?

The Power of Place

Speaking about Montpelier, historian Jon Meacham once said “if you want to understand the country, there are some places that you have to go.” Not because Montpelier is a glittering example of American exceptionalism or a whitewashed monument to a dead president. But because it has everything that America is in its truest and most vulnerable form. Some good, some ugly, some confusing, some painful, some inspiring.

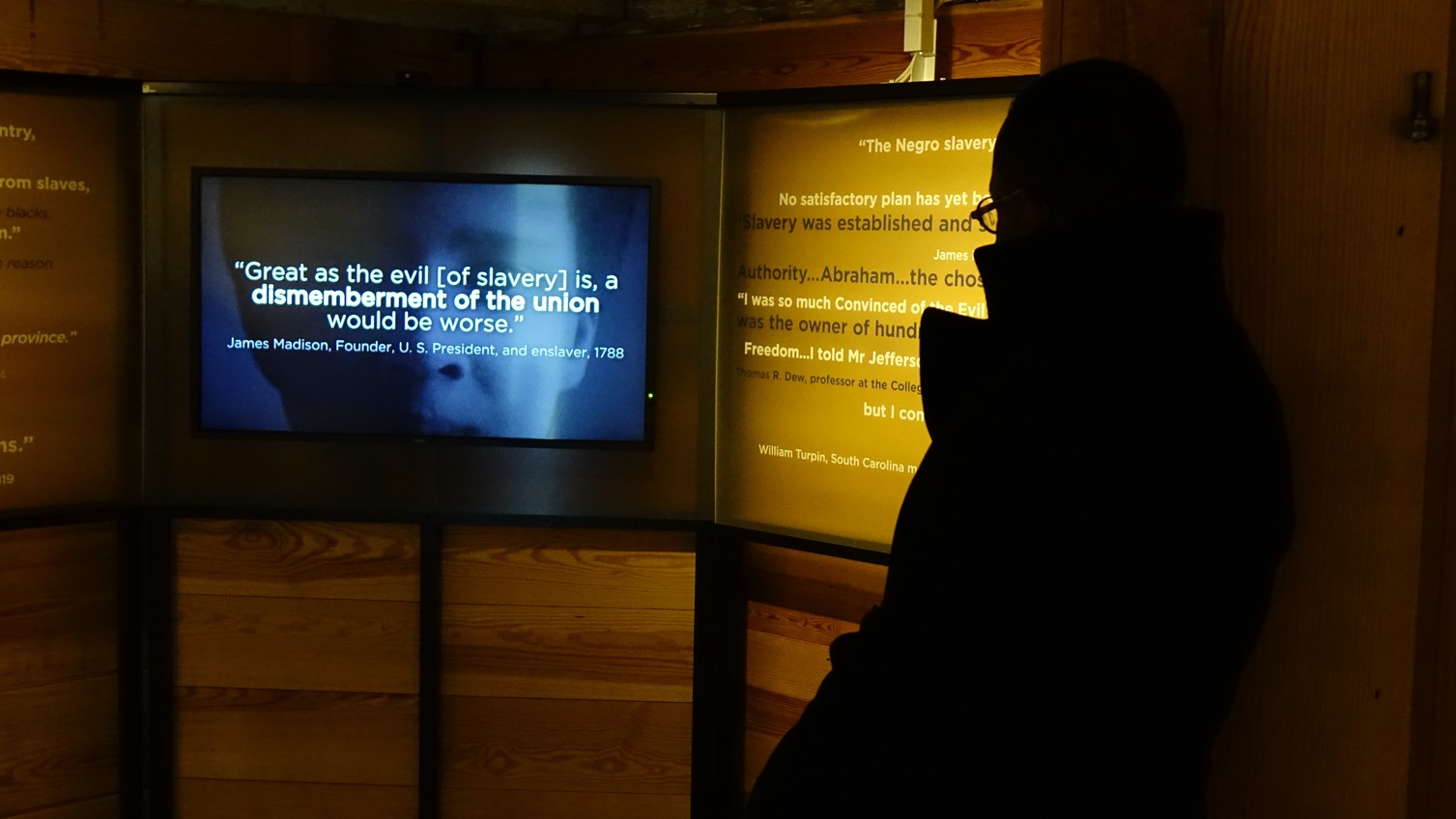

Summit participant experiences an interactive portion of The Mere Distinction of Colour (Kendall Madigan, The Montpelier Foundation)

Montpelier is an origin site of our national move towards self-government and the rule of law. It is also a site that exposes America’s tragic contradiction, a plantation where the legacies of slavery, the compromises of the Founders, and the failures of society over the past two centuries can be shown in stark relief. An understanding of that context is fundamental for unpacking the ways the conversation around race, rights, and equality has evolved. Montpelier’s exhibitions and tours are a powerful example of ways that museums and cultural institutions can be at the forefront of this conversation.

"E Pluribus Unum," by Rebecca Warde. Mosaic created from pieces of brick excavated at living quarters of enslaved men, women, and children across Montpelier. On many plantations, bricks were made by enslaved women and children. (Photo: Proun Design, courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation.)

“The Black experience in the United States is built on countless narratives; diverse experiences of community, activism, achievement and beyond,” said Brent Leggs, director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. “Through the Action Fund we strive to purposefully and respectfully engage the intellect and voices of those, to whom this history is the most personal, and who for too long have been silenced or omitted from the dominant narrative. Montpelier is the ideal place to have these conversations because of its historical significance, and the work the foundation is doing to uplift descendant voices to tell a more complete American story."

Why Now?

Until recently, museums and historic sites have fallen short in their inclusion of enslaved individuals and their descendants. Historic homes, many with direct connections to the institution of slavery, almost exclusively focused on fine and decorative arts, architecture, and the lives of wealthy white Americans. Very few institutions addressed slavery, and even fewer ventured into the legacies of slavery following the Civil War. Early efforts considered enslaved people in general terms, often focusing on labor and output, or through tours and exhibits separate from the main narrative. Enslaved people were rarely depicted as unique individuals with important identities beyond their labor. Since the early 2000s, many museums and historic sites have worked to interpret slavery more accurately. Sites have added furnished living and working spaces, programs, guided tours, digital apps, and better exhibitions. Despite their efforts, museums can still "intellectualize" slavery, approaching it as an academic subject and not as a massive trauma still affecting millions of human beings. For this reason, descendants of the enslaved don’t feel welcome in these institutions.

Montpelier descendant, Margaret Jordan, talks with Niya Bates during the summit (Andrew Shurtleff/AP Images for James Madison's Montpelier)

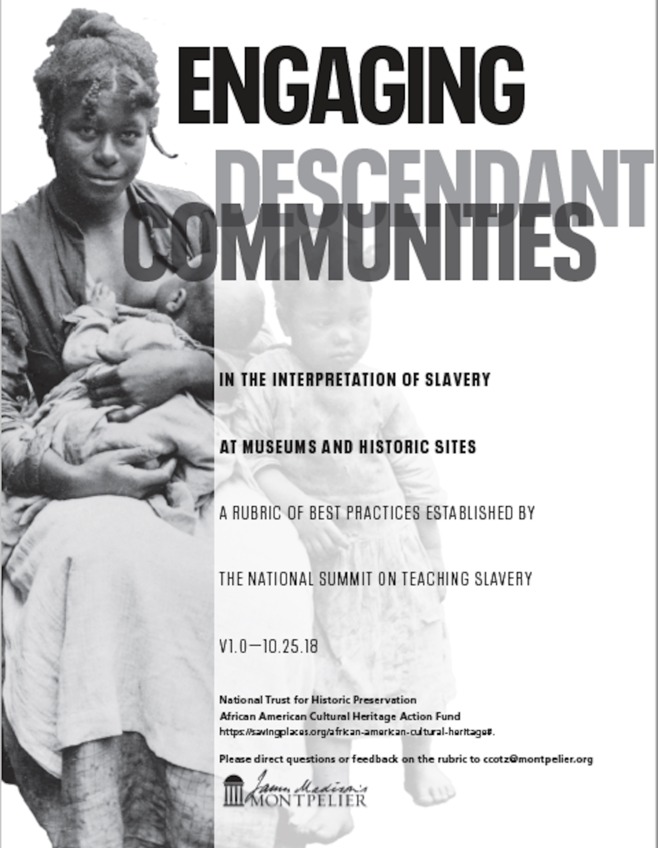

By the end of the weekend, Summit participants laid the framework for a document titled, “Engaging Descendant Communities in the Interpretation of Slavery at Museums and Historic Sites,” known colloquially as “the Rubric.”

The Rubric

The end product of the Summit, the Rubric builds a scalable methodology that sites can utilize to rate themselves as they engage descendant communities in their work. It contains concrete steps to ensure high-quality research, make connections and maintain relationships with descendants, and create inclusive, and accurate and empathetic exhibits and programs. It gives museums a place from which to start addressing difficult themes and traumatic legacies of slavery. Most importantly, the Rubric insists sites work with descendants of the enslaved at every step to ensure that they are interpreting slavery in a manner that is effective, informative, and respectful of the experiences of the millions of men, women, and children who were enslaved.

The Rubric from the National Summit on Teaching Slavery

The Rubric is broken out into 3 main themes: relationship building, historical research, and interpretation.

Relationship Building

Including descendants in the work of an institution is contingent upon building a positive relationship with the descendant community. If a museum or site already has a positive relationship with its descendant community, it must be maintained and nurtured so that it will continue to grow. Relationships are the foundation on which this work is done, and putting time, effort, and work into them is one of the most important steps an institution can take.

Not every descendant (or perhaps any descendants), will want to work with a particular institution that has a reputation of attempting to obscure or erase their ancestors’ pain and trauma. Descendants have historically been excluded from interpretation in museums, schools, and other forms of historical education, and often when they are included, they have been used only when convenient for the organization. It is essential for institutions to demonstrate respect for descendant communities and to approach interactions with sensitivity, humility, and cultural, social, and emotional awareness.

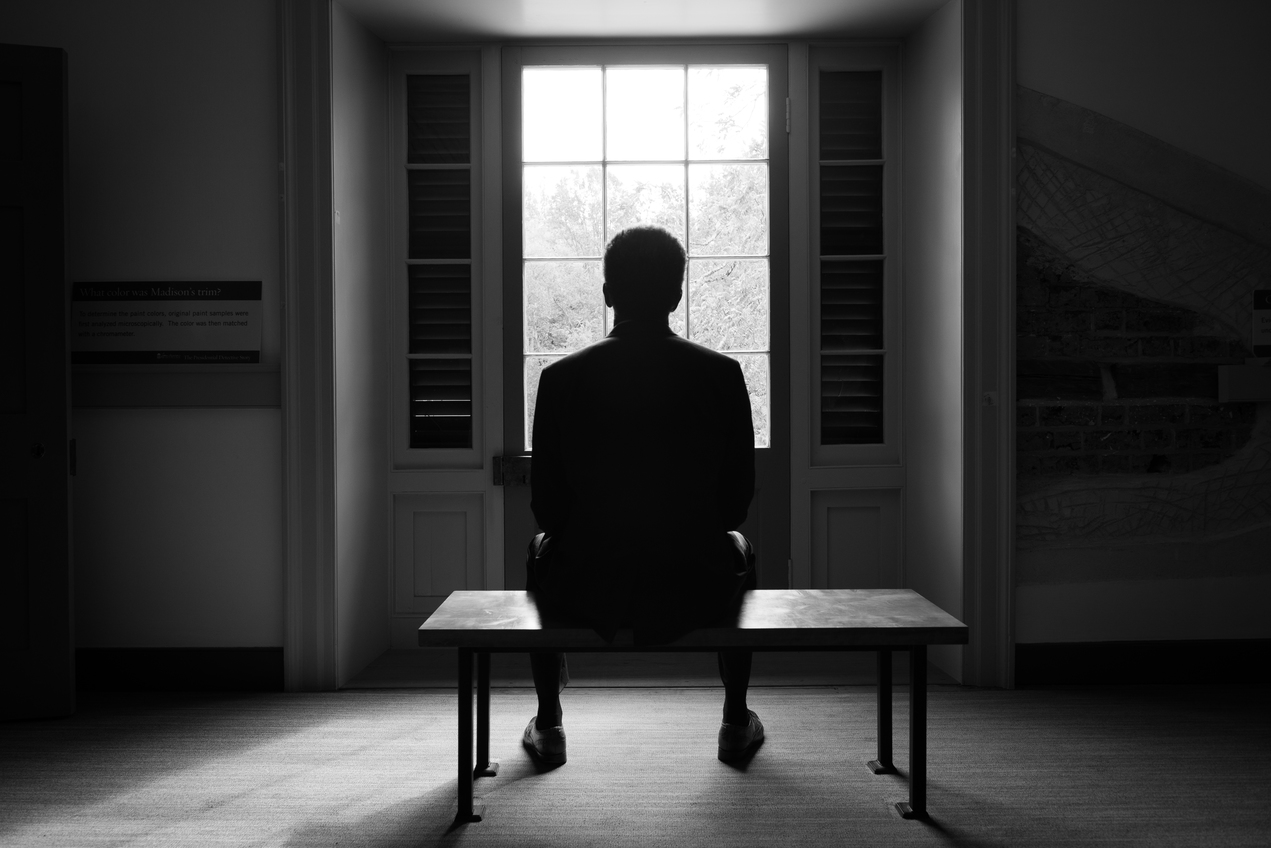

Director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at the National Trust for Historic Preservation and member of the Montpelier Descendant Community, Brent Leggs, looks out of a window of the Madison home at James Madison's Montpelier. Eduardo Montes-Bradley, courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation

What does a real collaboration with descendants look like? Ideally, descendants should be represented—and empowered—at every level of the organization, from the board to the volunteers. It may mean asking descendants: “Do you want these stories told? What is important to you?” A museum or site must realize that a community of descendants includes many opinions, thoughts, and feelings about what can and should be done. Institutions should be humble and aware of their histories, their legacies, and their reputations. Open lines of communication are necessary to build trust and inclusion with the descendant community.

Historical Research

To teach visitors effectively about slavery, institutions must start with research. In most museums and historic sites, this work is done exclusively by curators and exhibit developers. The Rubric urges sites to think differently and be more welcoming in the research process. Sites can easily collaborate with descendants of the enslaved as they collect and analyze sources including historical documents, archaeological excavations, oral histories, historic architecture, and artifacts. Museum staff and visitors can use this information to learn about the institution of slavery at their particular site and draw conclusions about larger themes such as cultural practices of enslaved people, consumer behavior, relationships of power, landscape changes, and diet (among many other topics).

Member of the Montpelier Descendant Community, Leontyne Peck, participating in archaeological examination at James Madison's Montpelier. Eduardo Montes-Bradley, courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation

Historic houses and sites can connect descendants with their ancestors. Historical research provides many opportunities for descendants of the enslaved to partner with museum staff in the process of discovery, analysis, and interpretation. Descendants can share their own oral histories, genealogical records, and family heirlooms - personal connections that add depth, humanity, and credibility to institutions.

Interpretation

The “Teaching Hard History: American Slavery” report concludes, “The nation needs an intervention in the ways that we teach and learn about the history of American slavery.” While this study addressed the teaching of slavery in America’s schools, it is equally applicable to museums, historic sites, and other cultural institutions.

Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. Southern Poverty Law Center

Museums and historic sites use a variety of methodologies to educate and engage with their visitors. These include tours, gallery exhibitions, field trips, public programs, and, more recently, online interaction between museum staff and the public on social media platforms. The Rubric demands museums be self-reflective. Staff should consider what their interpretation is adding to visitors’ knowledge and whether or not it adds context to modern-day conversations and controversies about slavery and race.

The interpretation of slavery in a museum setting is an opportunity to make an institution as empathetic and compassionate as possible. Tours, exhibitions, and online interaction should reflect agency and humanity, cultivate empathy in visitors for the people of the past, and emphasize the relevance of history today. Summit participants strongly recommended that museums and historic sites always invite descendants to collaborate with them as they plan, develop, implement, and evaluate their interpretation of slavery. Descendant involvement creates new possibilities and offers a different view of the world. It makes institutions stronger and more relevant to the broader community.

What's Next

Conversations around race, history, and justice continue to dominate our news cycles. Communities across the country wrestle with ways to address the presence of over 700 Confederate monuments, 551 of which were installed as statements of white supremacy decades after the end of the Civil War. Disparities based on race are evident in everything from incarceration statistics to housing to education. Boldly and honestly addressing the history of slavery is a necessary step for museums and historic sites - places still valued as credible in the era of “fake news.”

Implementation of the Rubric's practices are essential for museums and historic sites if they wish to engage effectively and ethically in much-needed truth-telling about slavery’s role in the shaping of the United States, the legacy it continues to have on race relations in America today, and the lingering disparities that prevent all Americans from realizing the ideals expressed in our founding documents. This Rubric marks the start of institutional self-examination for gauging the honesty and inclusiveness of their historical interpretation, and holding themselves and their peers accountable. With the help of the Rubric, museums and historic sites can lead the way towards a more honest and equitable future.